Street dogs and public health in India: The evidence base

The safety of our public spaces is of utmost importance, especially in densely populated regions such as Delhi- NCR. In recent years, there has been increased debate in public platforms such as the media and through litigation on the risks posed by street dogs to human health and safety.

In its recent order, the Supreme Court has emphasised the need to reduce risks to public health and safety linked to street dogs. However, the research evidence base suggests that the proposed measures will not achieve the desired public health outcomes.

What research shows

Rabies is very much a preventable disease if the correct health measures are in place. Long-term research shows that the most lasting and efficient way to prevent rabies is to combine universal, free, post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) for all bite victims with mass vaccination of dogs. India has made remarkable progress in rabies prevention in the last two decades. Estimated human rabies cases have substantially declined (by nearly 75%). Reported human rabies cases have dropped from 274 in 2005 to 34 in 2022. Behind these numbers are invaluable lives saved, thanks to improvements in post-exposure prophylaxis and animal vaccination drives against rabies. Yet, for many people, timely access to appropriate PEP and vaccine schedule adherence remain major challenges [1]. Therefore, rabies continues to be a serious problem.

Bites, mauling and injuries due to dogs remain concerns because there has been almost no attention given to other key health measures, namely, bite and injury prevention education, environmental management to prevent food waste accumulation, and the stable maintenance of appropriately socialized and vaccinated neighbourhood dogs, including targeted behavioural interventions to address conflict situations.

Will culling or removal solve the problem?

Street dog elimination, whether through removal or culling, may seem like a quick fix, but evidence shows that it is counterproductive from a public health perspective. In the short term, it results in the movement and influx of unfamiliar street dogs from other areas to occupy the vacated ecological niche, increasing the risk of bites and rabies.

In the longer term, the elimination of street dogs creates ecological gaps that are filled by other animals – often those perceived as even more threatening to humans. In countries such as the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada where street dogs have been eliminated through historical and ongoing removal and culling, animals such as foxes, coyotes, skunks, raccoons, coywolves, bears and gulls have occupied the vacated ecological niches. These animals generate similar public debates about risks to human health.

In the US, the rabies virus has adapted to other animal reservoir hosts with bats, raccoons, skunks and foxes now accounting for more than 90% of reported cases of animal rabies. Despite these animal reservoirs, human rabies cases in the US are low thanks to sustained pet and wildlife vaccination and effective PEP programmes for people: around 100,000 people require rabies PEP every year in the US, which is a reminder that prevention efforts must be constant and well-resourced.

Interestingly, countries without street dogs are not free from dog-related injuries or fatalities. Patterns of dog breeding, ownership and confinement create their own risks. In England and Wales, for instance, non-fatal hospital attendances due to dog bites and injuries rose by 88% from 2007 to 2021-22, while registered deaths increased from 0 in 1981 to 16 in 2023 (up to September).

Community-based studies reveal a more nuanced picture of dog bite risk than public debates often suggest. Research in New Delhi (n=2887; in 2014) [2], and Cheshire, UK (n=694; in 2015) [3], present surprising results about dog bites. In Cheshire, 24.78% of participants reported having ever been bitten by a dog in their lifetime whereas in New Delhi, 6.33% of participants reported the same, much lower than in Cheshire.

Incidence of dog bites (bites in the previous year) was 18.7 per 1000 population in Cheshire, and 25.2 per 1000 population in New Delhi, the latter being only slightly higher than in Cheshire. In an extensive nationally representative, community-based survey [4] across 15 states in India (2022-23), dog bite incidence was 4.7 per 1000 population (weighted incidence was 5.6 per 1000 population), lower than in Cheshire, UK.

The continued prevalence of dog-related injuries and deaths in countries that have eliminated street dogs has multiple interlinked causes. Owned dogs are often bred and trained to be aggressive towards people other than the owners. Confinement and lack of stimulation adversely affect their physical welfare and behaviour. This, combined with unrealistic expectations that dogs will be able to accept and tolerate anything imposed on them by their owners and others, result in situations that pose serious health threats to people.

The coexistence skills of street dogs

Street dogs have evolved naturally in human-dominated landscapes. Most street dogs have the skills required to cohabit safely and harmlessly with people, including those who dislike or are afraid of them. Research on street dogs and public health carried out by the University of Edinburgh and collaborators shows that human-street dog interactions in India are predominantly uneventful. In 82% of ROH-Indies study observations, street dogs were either approachable or exhibited neutral behaviour towards our research team.

However, public and media debates are centred on bites, rabies and mauling and are not representative of ground realities: such problems form a very small proportion of what happens on an everyday basis; our observational research in public areas in multiple cities shows that only 2% of all human-street dog interactions were antagonistic (e.g., angry barking, chasing or biting).

Public opinion: More moderate than headlines suggest

Public debates are disproportionately influenced by the minority of people who have strong negative views about street dogs. Our representative sample surveys in urban and rural India (Chennai in 2019 and Jaipur and Malappuram districts in 2025; n=5100) show that it is only a minority that hold strongly negative attitudes towards street dogs.

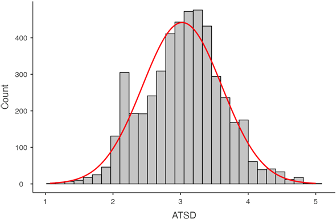

Across our combined Jaipur and Malappuram samples, attitudes towards street dogs are generally moderate, with few respondents expressing extreme positions. Scores on a composite measure of attitudes cluster around the midpoint of the scale, with attitude towards street dogs (ATSD) scores normally distributed around a mean of 3.02. In Chennai, ATSD scores were normally distributed around a mean of 3.07. This pattern suggests that, on average, residents of these regions hold mixed or moderate views towards street dogs, rather than strongly positive or negative positions.

Street dogs are seen as an integral part of local communities (67% in Jaipur; 48% in Malappuram; 55.5% in Chennai) and part of nature (78% in Jaipur; 58% in Malappuram). In Jaipur and Malappuram people report that the presence of street dogs makes them feel safe (49% of respondents) as they offer protection from strangers and predators. This figure was notably higher in urban areas (69% in municipal corporations or municipalities; 76% in Town Panchayats).

Over 60% of all our study’s observations of interactions in public areas recorded ordinary people providing affection or care to street dogs. In our sample surveys, 59% of the sample (68% in Jaipur; 46% Malappuram) agree they feel sympathetic towards street dogs. In Chennai, 79.3% agreed that street dogs are vulnerable animals.

Animal welfare organisations, including in New Delhi, are able to function only because a mass base of ordinary members of the public report or bring street dogs to them for treatment or neutering and vaccination. It is therefore incorrect to characterize concern and care for street dogs as restricted to animal activists.

Across our combined Jaipur and Malappuram samples, there was strong support for vaccination and neutering programmes – 86% agreed that street dogs should be vaccinated, and 66% supported neutering. In Chennai, 55.4% supported vaccination and neutering. By contrast, there was little support for eradication/culling policies, with more than 70% of respondents disagreeing that all street dogs should be killed. Notably, opposition to eradication policies was actually higher (77%) amongst those who reported that they or their children had ever been chased or bitten by a street dog (Jaipur and Malappuram). Any public support for elimination has always been marginal and fleeting, and usually in response to isolated, extreme events.

Public health and safety are contingent on putting in place all the measures essential for safe cohabitation with community dogs. Universal, free, and easily accessible post-exposure prophylaxis, mass dog vaccination, food waste management, community education, and responsible caregiving focused on conflict prevention are crucial elements of an evidence-based public health approach to street dogs. Cities and villages thrive when public health measures are rooted in science, implemented consistently, and supported by communities.

Cited references

[1] Lodha, Lonika, Ashwini Ananda, and Reeta S. Mani. 2023. ‘Rabies Control in High-Burden Countries: Role of Universal Pre-Exposure Immunization’. The Lancet Regional Health – Southeast Asia 19 (December):100258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lansea.2023.100258. Also Thangaraj et al. 2025.

[2] Sharma, Shantanu, et al. “Prevalence of dog bites in rural and urban slums of Delhi: A community-based study.” Annals of medical and health sciences research 6.2 (2016): 115-119.

[3] Westgarth, C., Brooke, M. and Christley, R.M. (2018) How many people have been bitten by dogs? A cross- sectional survey of prevalence, incidence and factors associated with dog bites in a UK community. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 72(4), 331-336.

[4] Thangaraj, Jeromie Wesley Vivian, Navaneeth S Krishna, Shanmugasundaram Devika, Suganya Egambaram, Sudha Rani Dhanapal, Siraj Ahmed Khan, Ashok Kumar Srivastava, et al. 2025. ‘Estimates of the Burden of Human Rabies Deaths and Animal Bites in India, 2022–23: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional Survey and Probability Decision-Tree Modelling Study’. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 25 (1): 126–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00490-0.

Addendum to the statement

Is there a ‘growing’ street dog problem?

Over the last two decades, coinciding with halting of dog culling in 2001 and with improvements in PEP for dog bites, human rabies cases in India have dropped sharply, by around 75% based on estimated numbers of cases, while reported cases have declined from 274 in 2005 to 34 in 2022.

Dog bite numbers (pet and street dogs combined), as recorded by the Integrated Disease Surveillance Programme, have also declined from 75,66,467 in 2018 to 37,15,713 in 2024 across India. Delhi saw a drop from 1,07,642 in 2018 to 25,210 in 2024. As of now, there is no separate data available for street dogs. It is also unclear whether dog bite data from the IDSP is specific to dogs or to all animals; recording protocols at the level of health facilities have been inconsistent till recently. Extensive, nationwide epidemiological surveys show a decline in annual dog bite incidence from 15.9 per 1000 persons in 2003 to 5.6 per 1000 persons in 2022-2023.

Street dog population numbers are hard to assess. They are often based on modelling that relies on incorrect assumptions about the survival rates of pups, i.e., that every pup survives, and street dog populations increase exponentially. The reality is that most pups born on the street die before they reach sexual maturity.

The Indian Livestock Census, which relies on community-sourced data, reflects this: 15.3 million were street dogs, a 10.67% decrease from the 2012 census figure of 17.1 million street dogs.

A key point to bear in mind is that declines or increases in population numbers, and bites or rabies cases can be evaluated only by looking at trends over time; fluctuations over shorter periods of a few years do not reflect a pattern.

The data that was used to pass the recent SC judgment was restricted to the period between 2022 to 2024 (and January 2025), which is not an adequate time period to assess effectiveness of current health strategies. The variation seen in this period could be because of the combination of a range of factors, including random fluctuations, improved reporting systems, changes in caregiving practices, and an increase in owned dog populations [2], especially dogs intentionally bred and socialised for aggression, and those kept in high-stress, low-welfare conditions.

Baseline data and changes in levels of reporting

At smaller scales, such as the city level, the absence of reliable long term baseline data makes it difficult to evaluate claims about increasing dog populations. The same applies to mauling and serious injuries which are much more likely to be reported and come to wider attention in recent years, with the widespread use of the internet, than they were before. Going by the decline in human rabies and bite cases and dog population numbers, it is more likely that the overall numbers of serious injuries related to street dogs has declined – even if they are reported more frequently.

Why do we still see health problems linked to street dogs?

If India continues to have a rabies problem, it is because of serious inadequacies in PEP provision. Recent research [1] shows that even healthcare workers are not fully informed about appropriate PEP protocols for rabies prevention, including the importance of wound washing, site of administration, and the type of PEP that is needed for different wound categories and bite circumstances. Availability, especially of monoclonal antibodies and/immunoglobulins, cold chain maintenance, and vaccine schedule adherence, are other pressing issues that need urgent action.

Bites and serious injury prevention have also not received adequate attention. ROH Indies research shows this requires measures based on a thorough understanding of the socio-ecological dynamics of modern cities, towns and villages: these include environmental management to prevent excessive concentration of food and other resources; chasing and bite prevention education; community engagement for responsible caregiving, and targeted interventions for conflict mitigation that are tailored to the specific context and locality.

Cited references

[1] Lodha, Lonika, Ashwini Ananda, and Reeta S. Mani. 2023. ‘Rabies Control in High-Burden Countries: Role of Universal Pre-Exposure Immunization’. The Lancet Regional Health – Southeast Asia 19 (December):100258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lansea.2023.100258.

[2] Brill, G.; Chaudhari, A.; Polak, K.; Rawat, S.; Pandey, D.; Bhatt, P.; Dholakia, P.K.; Murali, A. Owned-Dog Demographics, Ownership Dynamics, and Attitudes across Three States of India. Animals 2024, 14, 1464. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14101464